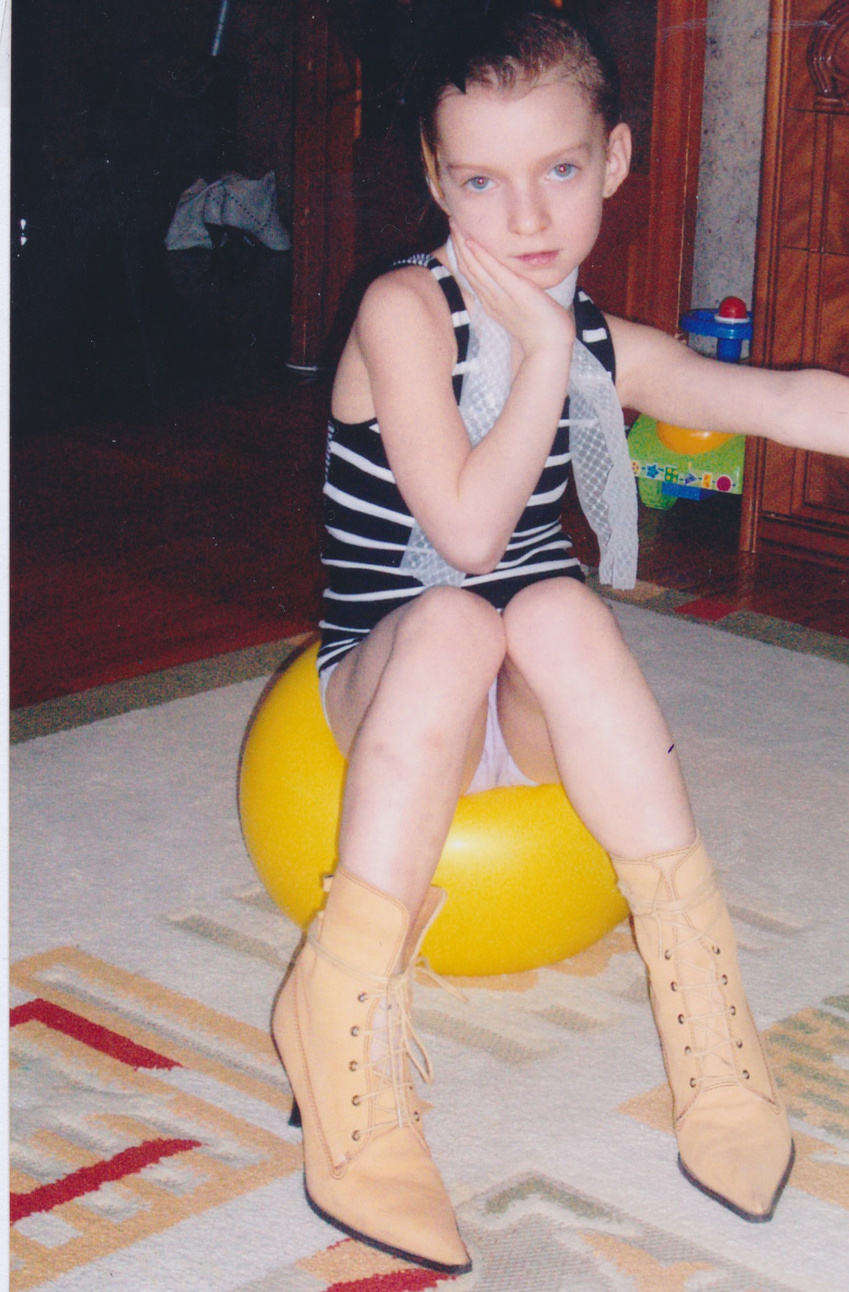

Nina Gubskaya

High-school student

Lives in Moscow

Before I moved to Moscow at 14 with my parents and my younger brother and sister, we lived in the Siberian city of Surgut.

My mother has worked as a hair stylist for over 20 years, and my father has had different jobs — as chief editor of a political newspaper, a television host and a political scientist. They moved to Moscow for their careers.

It was a huge turning point in my life; everything changed. Surgut is a small, isolated city where people are narrow-minded. If I went there now and told people about my gay friends in Moscow, they would be shocked. They would laugh if I told them about my weekends spent at techno clubs or my interest in fashion. Every time I come back to Moscow after a visit to Surgut I realize I have everything: the freedom to do whatever I want.

My parents mostly let me do what I want. I tell my mum matter-of-factly that I’m going to a techno party. I’ll write to her every hour: "Mum, everything’s good here, the music is great," or I’ll send her a few pictures with my friends.

I move in different social circles and people often call me “Nina the party girl” or “Nina the ‘techno cobra.’” The Afisha magazine once had a quiz on how well you know the Moscow club scene, and my result was “Techno Cobra.” The name has stuck ever since.

I’ve been going to techno clubs since I was 14. “Face control” is strict here in Russia, but I always stood firm with a glamorous face and they’d let me through. Now most of the bouncers know me.

When I was 16, I started dating a guy 10 years older than me. It was strange — my dad was not happy about it, but then they started getting along. We belonged to absolutely different generations; I would tell him stories from my world, he would tell me stories from his.

I don’t really look my age — I have a sort of “resting bitch face.” But really I am just vulnerable and sensitive and I've created a shell around myself. In the 10th grade, when I switched to a new school, nobody spoke to me because they thought I was a glamorous moron. But now I’ve adapted and nobody is afraid to talk to me anymore.

I initially wanted to study journalism and did an internship for a fashion magazine. It was a good experience because I realized that every job can become routine. You show up to a magazine thinking you’re going to be writing about something extraordinary, like about the evolution of fashion in the 1970s, but then they tell you to write about Kim Kardashian’s breasts.

This is the way it is. Take a tattoo artist who loves drawing intricate tattoos: A girl comes in one day and asks for a heart, and the tattoo artist thinks to himself, “Am I really about to draw this girl a damn heart?”

After college I want to be a producer. This is the ideal job. You have an idea, and then you have designers and programmers to execute it.

I like being Russian. Russia has unique stereotypes that don’t exist anywhere else, like pickled tomatoes, bears and the balalaika. Take the designer Gosha Rubchinsky, with his “gopnik” [Russian for thug] fashion. For Europe this is an innovation, but we see this every day on the outskirts of Moscow.

I feel proud to be associated with quirky stereotypes. I wouldn’t like to be American.

Russians love to scold Russia. It’s like with a family — you scold your brother, but you’ll still tell others how much you love him. We might not have this thing or that thing — there are imperfections here. But still, when we talk to foreigners, we’ll boast about our cultural grandeur.

My grandmother used to recite this poem: “I’m a little girl, and I don’t go to school / I’ve never seen Putin, but love him I do.”

Putin is just my president. It’s fine. But I don’t really think the youth is interested in politics.

There is always hype around the image of Putin. Last summer, my friends and I bought purses and shirts with his face on them and went to clubs. Now that I’m seeing shirts of Ksenia Sobchak for sale on the streets, I want one too. It’s just hype; trends infused with a bit of patriotism. But in my opinion, it doesn’t matter who is in power — Putin, Sobchak, Alexei Navalny — nothing will really change. When Dmitry Medvedev was president, did anything change?

I don’t really know what I’d change in my country. I’m 18 and I live an energetic and comfortable life.