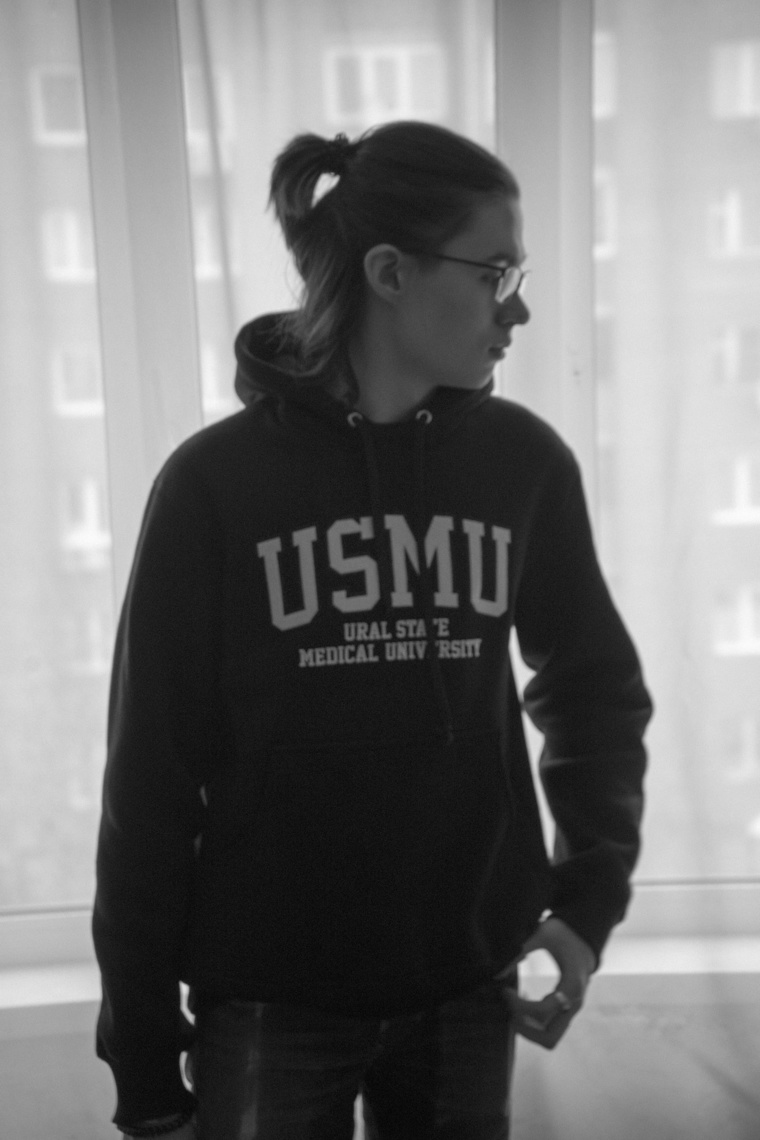

Vladimir Gistsev

Studies clinical psychology at Ural State Medical University

Lives in Yekaterinburg

I was born and raised in Zheleznogorsk, a closed city about 40 kilometers from Krasnoyarsk. My parents ended up there in the 1990s because they were invited to work for a firm that manufactured satellites.

The city is surrounded by a barbed wire fence, and outsiders need special government-approved passes to be allowed in. It’s not so much that the residents are closed off from the outside world, like in North Korea, it’s more that the outside world doesn’t have access to us. Nevertheless, living with so few people, enclosed by barbed wire, can certainly be depressing.

Being born in a city like that really leaves you with just two options: motivate yourself to leave, or remain there forever. I was lucky enough to take the first route, as were most of my friends.

I was a rather introverted child. I couldn’t really find a common language with my peers. Now I wear mostly dark clothing, and if I examine this through a psychoanalytic lens, it could be an extension of my introverted character. I was never really a normal kid or a rebellious teenager.

After my first romantic encounter at the age of 14, I started to become more sociable. We were on a school camping trip, sitting around a campfire grilling shashlik. I had a guitar, and I heard a voice behind me ask for a Nirvana song; I turned and saw her green eyes.

We dated for a few months, and we remain close friends to this day. All the time I spent with her helped me come out of my shell.

These days, my father works as an insurance agent and my mother is an accountant. I’m an only child. My parents went through turbulent periods throughout my childhood, but their relationship has stayed strong. Whenever they were confronted with challenges, they would work through them as a couple.

As banal as it sounds, I think mutual understanding and mutual care is the foundation of a good relationship. The standard Russian situation where the man comes home, beats his wife and drinks his beer while the woman prepares borshch for him and their four children doesn’t appeal to me at all.

When I was in high school, I would spend my weekends in Krasnoyarsk volunteering at a center for contemporary art. I like abstract art because it depicts images that aren’t apparent at first glance. For that reason, I am a huge fan of David Lynch — he evokes this feeling of complete uncertainty. And it is left up to the viewer to piece together his meaning.

I don’t like it when people begin to advocate certain points of view against their own common sense: someone who has always been tolerant toward religion reads social media posts about atheism and suddenly begins to hate religion. Or someone who has never had an opinion about the traditional domestic setting reads an article online and begins to hate family values. I am neutral toward all values — I don’t really like to have strong opinions.

Take the topic of homosexuality: I don’t think it is fair to smear someone for being gay and I personally am not against it. But you’ll never succeed in conducting scientific research on the roots of homosexuality because of the trend of tolerance pervading the internet. Any attempt to study homosexuality as a non-pathological phenomenon just won’t see the light. This happens on a global scale. I have never really noticed there being a stigma toward homosexuality in Russia, probably because I don’t watch any television.

Last year I moved to Yekaterinburg for my studies. I’m currently a first-year student of clinical psychology at Ural State Medical University. I guess I chose the field based on altruism: I want to help other people.

Since the Soviet Union, psychotherapy has been associated with psychiatric care and treating “disorders.” The idea that psychotherapy is an American scam, with therapists sucking you dry for simply wanting to talk about something, still pervades Russia.

But this seems to be slowly changing and psychotherapists are slowly becoming accepted as specialists. I think when I graduate in five years the field will be much more popular. In Russia, women still dominate in this line of work; the humanities are generally dominated by women here. But that doesn’t bother me.

If I had a choice between the same salary and line of work here or abroad, I would choose to live abroad, simply because the idea of interacting with new cultures appeals to me. I don’t think you can outright say that life would be “simpler” outside of Russia. Every place has its problems.

I don’t love Russia, I don’t hate Russia. I don’t understand this whole idea of “loving your homeland.” I am entirely politically neutral, and this trend of apathy defines my generation.

I’ll probably vote in the upcoming election, although I haven’t decided for whom yet. If the ballot was in my hand right at this moment, I’d probably just pick a name based on intuition.